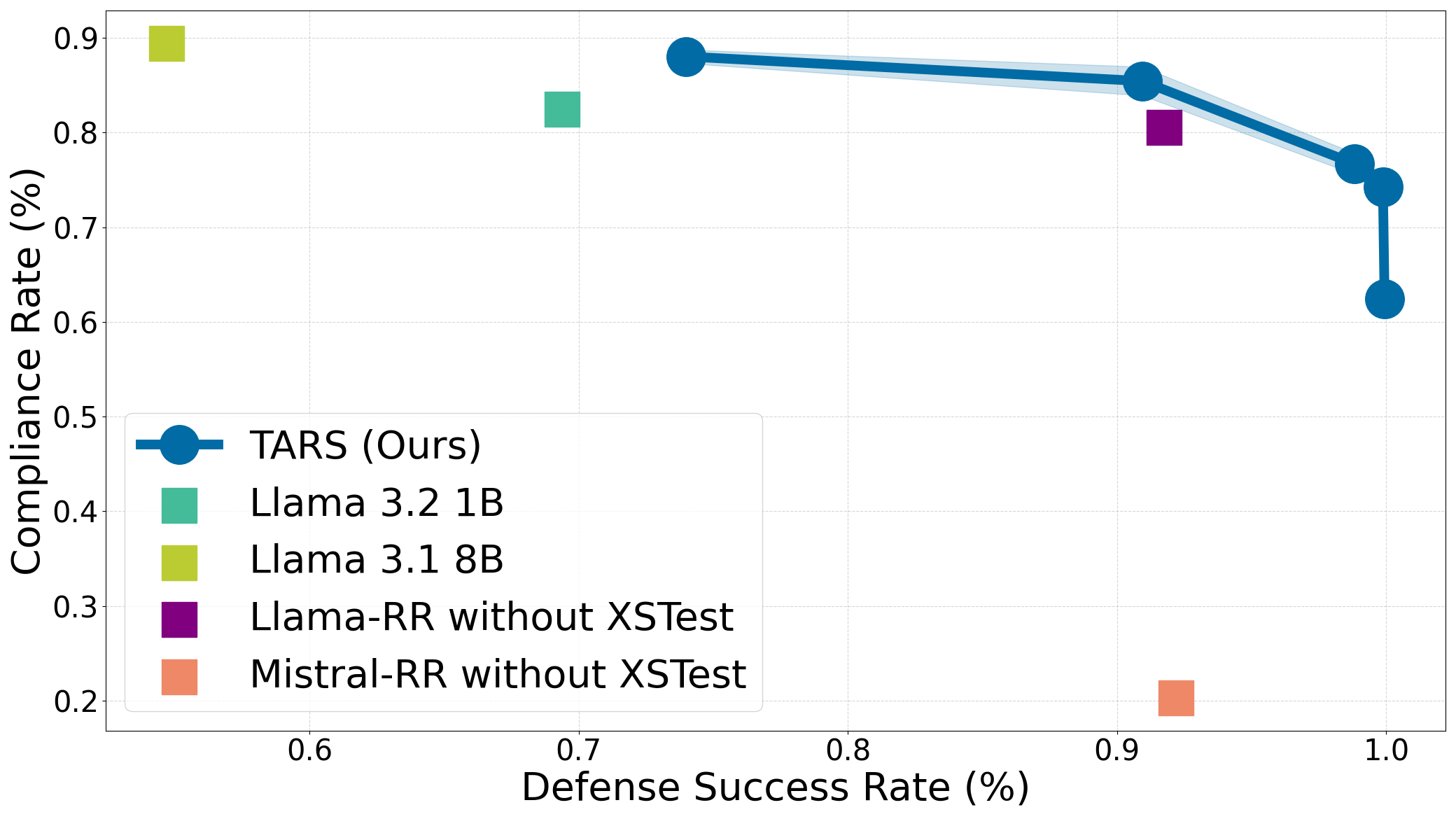

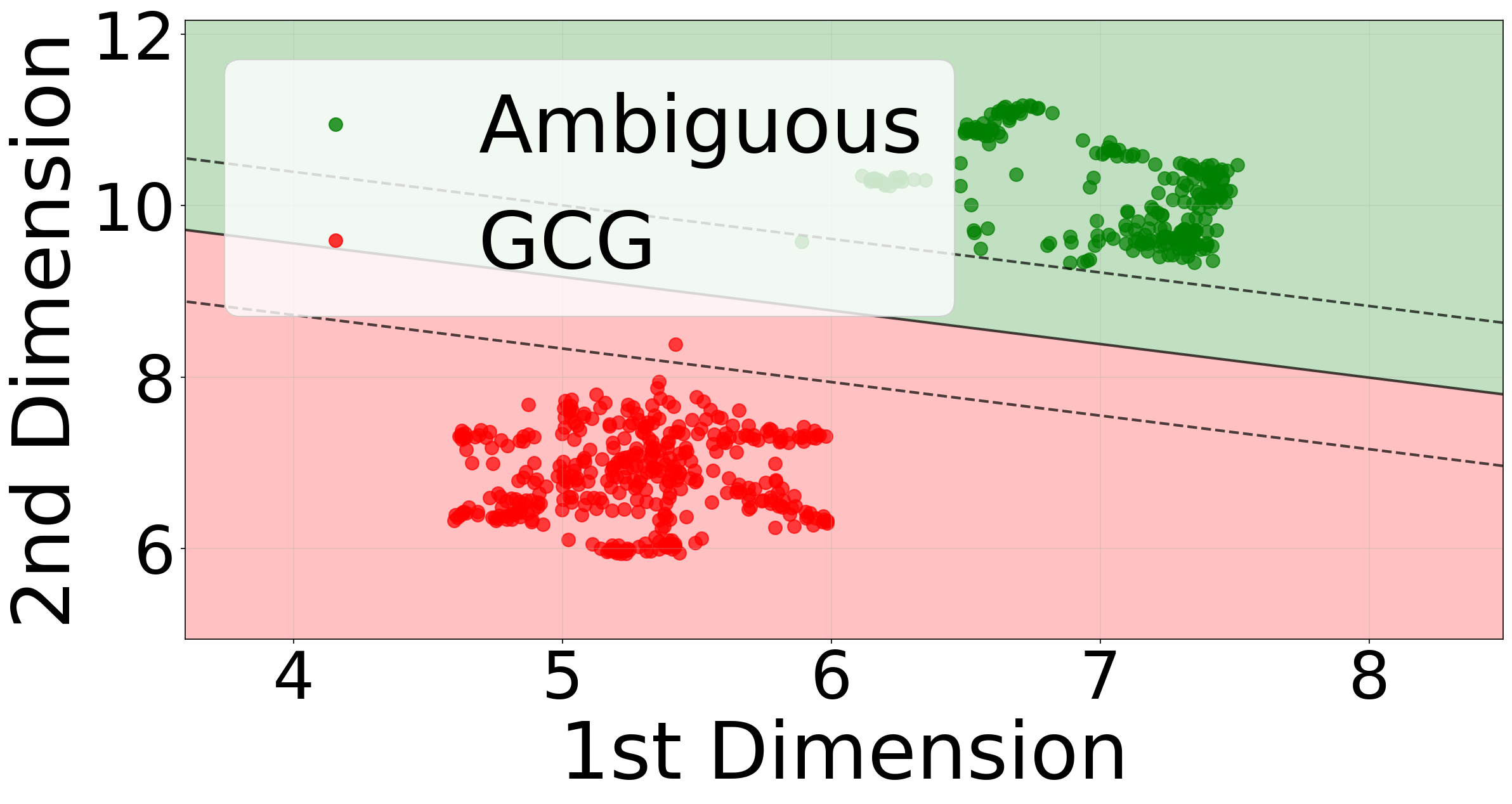

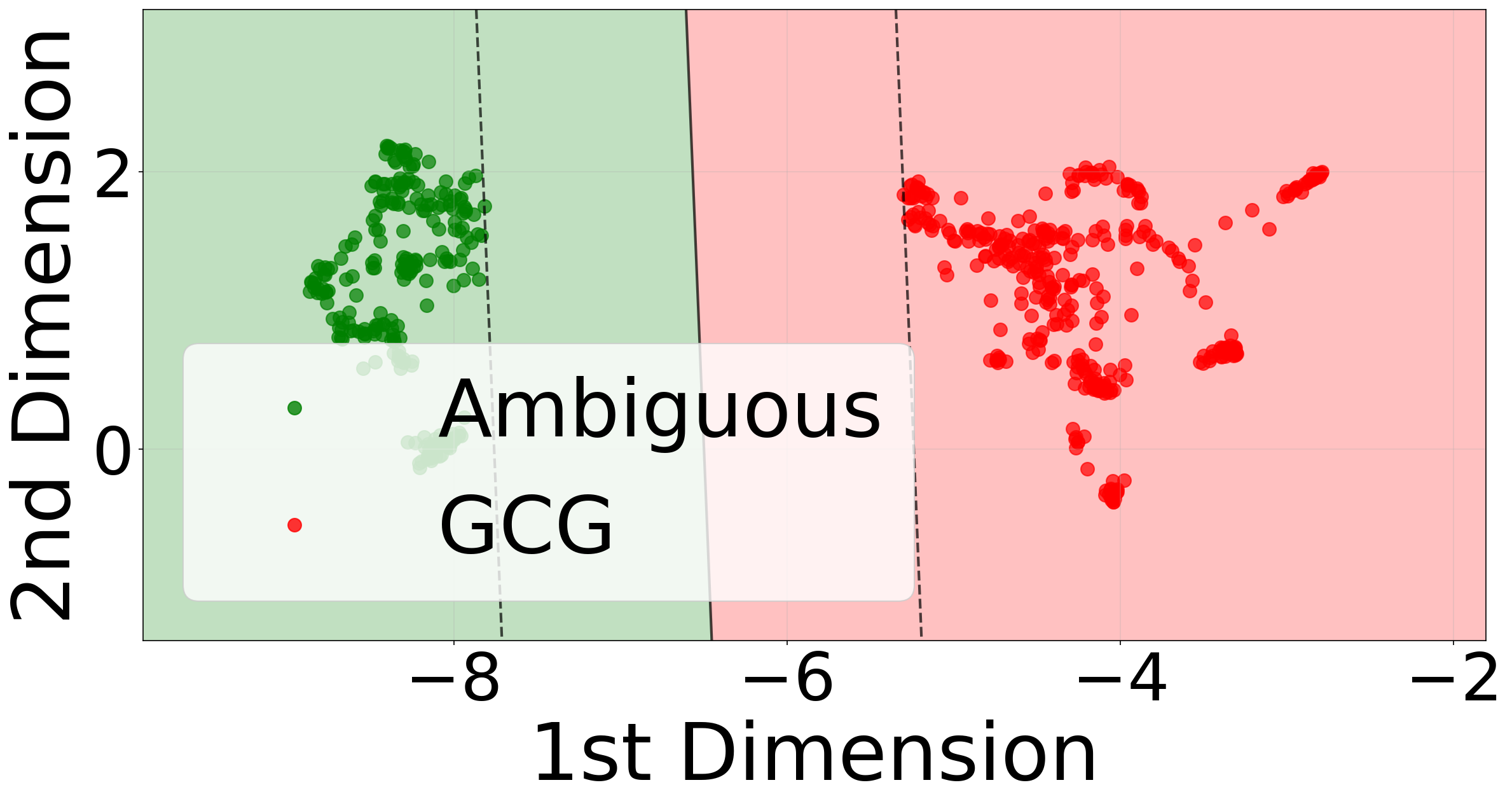

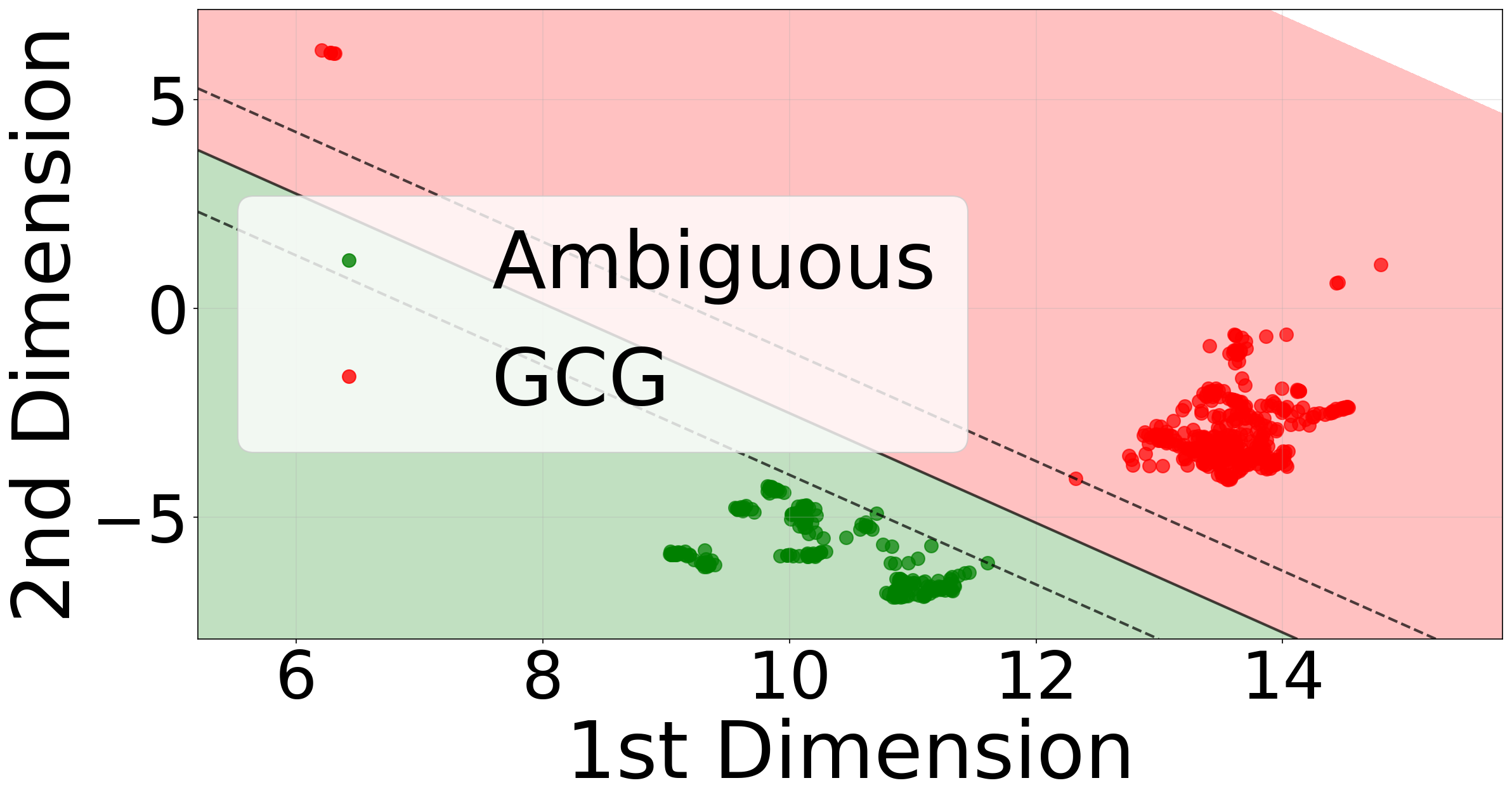

We compare TARS against existing defenses such as Deliberative Alignment (DA), Circuit-Breakers (Llama-RR, Mistral-RR), SafeChain, and RealSafe-R1, as well as open-weight models such as Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct. We evaluate for safety on Harmbench averaged across four attacks (GGC, PAIR, AutoDAN, PAP) and evaluate compliance on XSTest (left) and WildChat (right). TARS-trained models even at the 1.5B scale attain a better safety-refusal trade-off compared to other 7-8B models (Llama-RR, Mistral-RR, Llama-8B, and SafeChain), not to mention TARS at the 7B scale outperforming all. TARS also beats circuit-breakers which is a SOTA defense that uses representation re-routing to make models refuse only on harmful prompts. Compared to previous reasoning defenses, TARS also achieves better performance than DA, which uses context distillation of rubrics/guidelines to help the model learn when and when not to refuse.

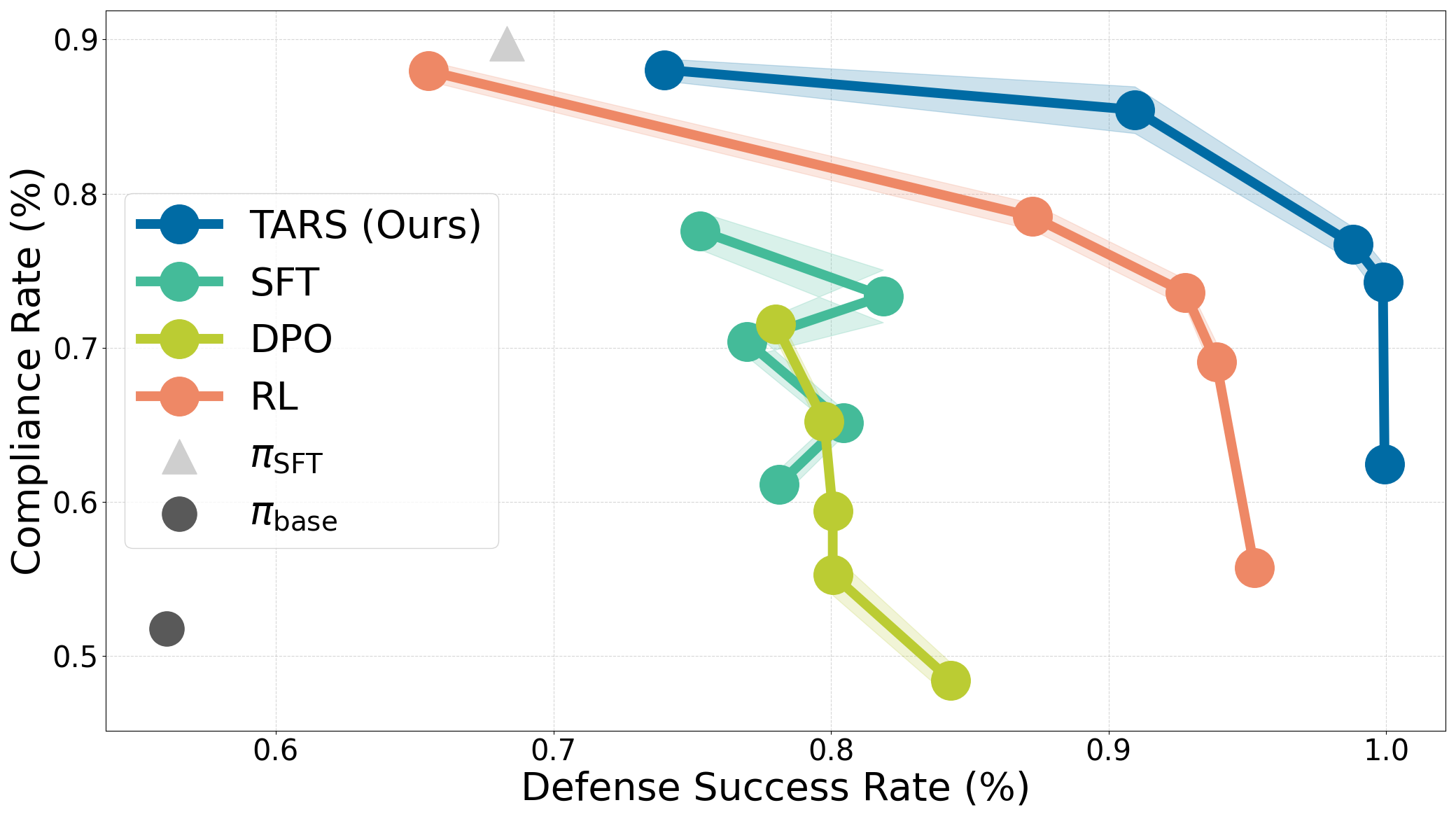

We also compare TARS with other training methods (SFT, DPO, and RL without reasoning). For a fair comparison, we train on the same prompts with a similar amount of compute. First, we find that both RL and reasoning are essential for improving safety while minimizing refusal. Second, we see that the initial SFT stage significantly reduces refusal by being helpful and slightly improves safety. However, it is the RL stage that learns to trade off helpfulness for safety. Third, RL without reasoning outperforms SFT with reasoning. Throughout our experiments, we consistently found that SFT struggles to generalize and easily overfits to in-distribution prompts. These problems were not solved even when training on additional SFT configurations including guidelines for context distillation. Thus, given both harmful and harmless prompts, exploring through a reward system (TARS/RL) better increases adaptivity to prompts compared to static reasoning traces (SFT/DPO).